Exhibit Introduction

On the evening of Monday, November 1, 1976, Air Force One, dubbed The Spirit of ’76 in the nation’s Bicentennial year, touched down at Kent County Airport. Following a hard day of campaigning in Ohio and Detroit, the President of the United States and the First Lady had returned home to cast their votes the next day in an election that would decide whether he would continue serving as President for the next four years. As recently as three years before, it was an election neither had contemplated.

The next day, President and Mrs. Ford joined over 39 million of their fellow citizens by casting their ballots for the man from Grand Rapids. Then they returned to the airport. But before leaving for Washington, they paused for a small ceremony to dedicate a mural to the city’s favorite son. Standing before the canvas that offered images of his youth, his family, and his career, President Ford’s eyes were drawn to the portraits of his mother and stepfather. “It really made me just get goose bumps all over,” he recalled. “I couldn’t help but look at their faces in the mural and wonder how they would have felt, the thrill they would have gotten out of it. Without a question, they would have been overwhelmed.”

Ford had returned to the town of his youth, looked upon the faces of the parents who raised him, and memories of growing up in Michigan rushed to meet him. This online exhibit uncovers the early life of Gerald R. Ford in his hometown of Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Gerald R. Ford's Life

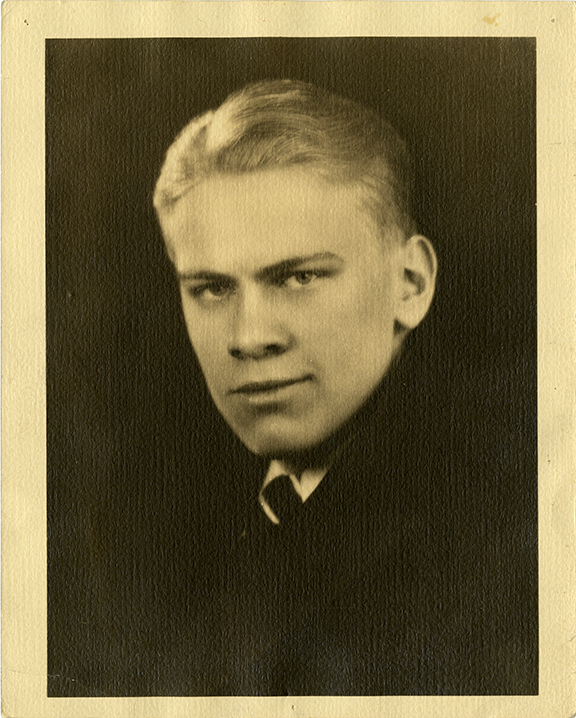

The 38th President of the United States was born Leslie Lynch King, Jr. on July 14, 1913, in Omaha, Nebraska. Though born in a different state, he was thoroughly a product of the city he grew up in: Grand Rapids.

Through the caring community and ethics of his hometown, the honest and hardworking values of his parents, and the discipline and support offered to him by academic and athletic opportunities, Gerald R. Ford's boyhood was formed, ready to meet the challenges that life would lay before him. Gerald Ford drew from the values and lessons of his youth as he restored the presidency in the wake of a scandal that left the nation reeling.

Jerry Ford's boyhood was marked by strong family ties, extracurricular activities, civic involvement, appreciation of nature, and eventually the competitive world of football and the gridiron. Each of these characteristics had a profound impression on the man that would eventually be president. Explore these aspects of the early life of Gerald R. Ford through the tabs and their submenus on the left, and see how Grand Rapids, and later the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, formed the man.

Ford’s life began in tumult. Although of a charmed and stable upbringing throughout the majority of his youth, his life began under dramatic circumstances; his mother whisked him away from her abusive husband just days after he was born.

Dorothy King settled in Oak Park, Illinois, living with her sister, before moving to Grand Rapids, Michigan into the home of her parents. There she would meet Gerald R. Ford, and together they would raise Dorothy's child and three more of their own. Junior, as the future president came to be known by family and friends, was put on a path that would lead to the highest political office in the land.

Flight from Omaha

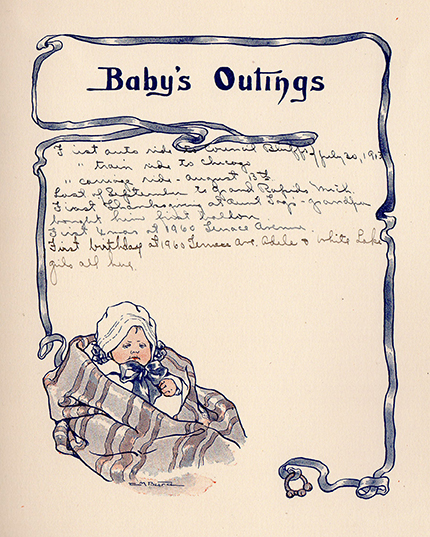

A page from a record book that Dorothy kept of Junior's first years, which document the fleeing of Omaha as his "first auto ride" to Council Bluffs, Iowa.

A page from a record book that Dorothy kept of Junior's first years, which document the fleeing of Omaha as his "first auto ride" to Council Bluffs, Iowa.

The man who went on to become the 38th President of the United States came into this world under tumultuous circumstances. His mother was married to an abusive husband, and just days after his birth, Leslie L. King, Jr. was brought by his mother from Omaha to a better life farther east.

His mother was Dorothy Gardner King, a beautiful woman hailing from a well-respected family in Harvard, Illinois. She had married the dashing son of a wealthy businessman, Leslie Lynch King of Omaha, Nebraska, in September of 1912. At the age of thirty, King was ten years older than his wife, but impressed by his charm and bravado, the age difference did not matter to Dorothy. King had secured the blessing of her father, Levi, assuring him of his financial prospects and that Dorothy would be well supported. Married in Harvard on September 7, 1912, the two were the epitome of a happy couple. A few weeks later, the Kings embarked on a luxurious honeymoon to the west coast, and it was there that Dorothy was first subjected to Leslie King’s surprising temper and physical abuse.

Her husband's violence did not subside once they returned to Omaha, eventually leading to King ordering his wife to leave the large Victorian mansion that belonged to his father Charles. After only seven weeks of marriage, Dorothy came home to her parents with news of the shocking turn of events. A few days later, a remorseful Leslie King showed up and begged her to return to Omaha. She consented on the condition that his behavior would improve and that they would move out of his parents’ home.

The birthplace of Gerald R. Ford, Jr., Omaha, Nebraska, with Dorothy's descriptive handwriting.

The birthplace of Gerald R. Ford, Jr., Omaha, Nebraska, with Dorothy's descriptive handwriting.

The couple moved out of Charles King’s house and into a shoddy basement apartment. Here Leslie King revealed that he was deeply in debt, and that he had lied to Levi Gardner about his ability to support a wife. Dorothy continued to put up with her husband’s wrath. During the Christmas holidays she learned that she was pregnant with a son. For the birth of the child, the couple moved back into the King mansion, and on July 14, 1913, the hottest day of the year, Leslie L. King, Jr. was born, named such at his father’s insistence. Dorothy’s mother, Adele, was present at the birth of her daughter’s child, but was ordered to leave by King once Junior was born. She refused despite Leslie's threats, as she was concerned for her daughter's health. In a call for help, Dorothy summoned her father to come and talk to Leslie.

On his arrival to Omaha, Mr. Gardner and his son-in-law agreed that the couple should separate. “The sooner they leave, the better," King insisted. As soon as Dorothy was well enough to travel, she would depart with the newborn son, and her mother and a nurse would take care of her in the meantime. Believing the problem to be solved, Levi Gardner left for Harvard.

Almost immediately, King demanded that Mrs. Gardner and the nurse leave the house. When they refused, he threatened them with a knife. Again, Dorothy telegraphed her father, but by the time he returned, King had obtained a court order that prevented the Gardners from seeing their daughter. A virtual prisoner, Dorothy fled the King mansion, hiring a driver to take her to Iowa, where her parents were waiting at the state line. Upon reuniting, they all took a train to Chicago on July 30th, less than a year after the marriage had begun. By December 1913, the Kings were divorced.

Beginning Anew in Grand Rapids

Gerald R. Ford, Jr., with the family dog, Spot and Peck, in Grand Rapids, 1915

Gerald R. Ford, Jr., with the family dog, Spot and Peck, in Grand Rapids, 1915

Following the separation of Leslie and Dorothy King, the latter temporarily stayed with her sister, Tannisse, and her husband in Oak Park, Illinois. There, she filed for divorce from King, who was found “guilty of extreme cruelty” and was ordered to pay three thousand dollars alimony and twenty-five dollars a month in child support until their son reached the age of twenty-one. Stubborn and deeply in debt, King refused to pay a dime. His father Charles was troubled by the situation, and agreed to pay the child support for Leslie, though the alimony fee remained. But the marriage was at an end, and Dorothy was able to carry on with her life.

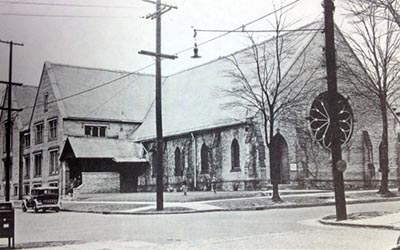

During this time, Dorothy’s parents moved from Harvard, Illinois, to Grand Rapids, Michigan, where Levi had invested in real estate. They invited their daughter and grandson to come live with them at 457 Lafayette Street. The city itself had a reputation for morality and prosperity--a great place to raise a family. No sooner had they arrived in the town on the Grand River had Dorothy met someone, a man named Gerald R. Ford.

She met him at a Grace Episcopal Church social event in 1915, and they quickly showed an interest in each other. Ford was a twenty-four year old bachelor who was considerate and even-tempered. Gerald's father, George Ford, moved to St. Louis in 1898, leaving his family in Grand Rapids. Gerald left school after completing the eighth grade to pursue a trade and help support the family, a responsibility made more immediate when his father was killed in a train accident in 1909. By the time he had met Dorothy, Gerald had a good sales job, selling paint and varnish to furniture factories in town. The two had a courtship that lasted almost a year, until they were married where they met, at Grace Church, on February 1, 1917.

Although he was not legally adopted by his new father, Leslie L. King, Jr. was now being called "Junior" Ford, and eventually, Gerald R. Ford, Jr. In every way that mattered, the man his mother married was his real dad. “He was the father I grew up to believe was my father,” said Ford, “the father I loved and learned from and respected.” After years of upheaval, Gerald R. Ford, Jr.’s place was now set.

Betty Ford once described her mother-in-law, Dorothy Ford, as the “perfect person to raise four very strong young men.” Dorothy was, by universal agreement, a “doer.” Her oldest son recalled that, “She not only worked awfully hard in the house…” but, “she was very active in numerous local organizations.” Such activity she had found in her parents, Levi and Adele Gardner. Both were among the founders of Harvard, Illinois. Adele was active in civic affairs, and Levi was a businessman and the town’s third mayor. By 1912 he and his business partner, L. H. Stafford, were in Grand Rapids developing real estate along Burton Avenue.

When Dorothy divorced Leslie King, she and her son first stayed in Chicago before moving to Grand Rapids to live with her parents. While attending St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, in the center of the city, she met Gerald Ford. After their wedding in 1917, they lived on Madison Street, in a duplex shared with Gerald’s mother and sister.

“She was a very loving parent,” Junior said of his mother. Dorothy was devoted to her husband and expected much of her children. “She was, in a firm but nice way, a disciplinarian,” said Ford. And the many qualities that endeared her to those who knew her, she passed on to her children. “I would say that most of the good characteristics I have, whatever they are, I inherited from her,” Ford recalled.

Gerald Ford, Sr. grew up in Grand Rapids, a city that still reflected much of its frontier and agricultural roots, but also one that was investing more deeply into industry, especially furniture manufacturing. This transition was being furthered by railroads.

In 1903, Gerald left school after completing the 8th grade. This was not unusual in those days, when parents had to decide whether their child would pursue a trade or a college degree. Gerald worked as a cashier for the Grand Rapids, Holland, and Chicago Railway, selling tickets to those traveling to the Windy City.

By 1914, he began his career in paint, working as an assistant sales manager for the Alabastine Compan, selling an inexpensive whitewash used on interior walls. Shortly after he married Dorothy, he took a job as sales manager for Heystek & Canfield, a paint production firm that sold their product to contractors and furniture manufacturers. In the early 1920s he would become a salesman for the Grand Rapids Wood Finishing Company and from there start his own business-- Ford Paint and Varnish.

As an adult, he stood 6’ 1” and was often described as the straightest-standing man around. “Kept himself in good physical condition,” his step-son remembered. “He had jet-black hair, which he combed in a pompadour with a part down the middle,” said Junior, who would comb his hair the same way.

Ford Sr. loved to hunt and fish. “I used to try both with him, but I had no interest, so we kind of didn’t get together on that,” Junior recalled. But Dad and son got together on so much more. They played baseball together, and Senior took an active interest in Boy Scouts with each of his sons, seeing three attain the rank of Eagle. “He went to every high school and college football game I played in, in the state of Michigan,” Junior said. Senior taught his step-son the virtues of hard work, civic responsibility, and personal integrity. “Whatever he got into, he was highly regarded and eventually chosen for some position of responsibility.”

The Ford men sitting on the front step of 649 Union, 1927. Left to right: Thomas Gerald Ford, Gerald R. Ford Jr., Richard Addison Ford, Gerald R. Ford Sr., and James Francis Ford seated on his father's lap.

The Ford men sitting on the front step of 649 Union, 1927. Left to right: Thomas Gerald Ford, Gerald R. Ford Jr., Richard Addison Ford, Gerald R. Ford Sr., and James Francis Ford seated on his father's lap.

Ford’s first boyhood home stood at 716 Madison Avenue, in an established neighborhood in southeast Grand Rapids. His father was prosperous during this time, and eventually earned enough money to put money down to build a house on Rosewood Avenue in the affluent East Grand Rapids suburb. The Fords moved into that newly built house in 1922, but they were not able to enjoy it for long. The owner of Heystek and Canfield, the paint and varnish business that employed Gerald Ford Sr., had died, and the new management made a series of poor choices that led to many managers losing their jobs in the company. Ford Sr. was one of the unfortunate employees. “Well, I guess I’ll just have to work harder,” he told his wife.

Though Ford quickly found work at another company, it was at a lower salary. The family realized that they would be unable to maintain the payments on the new house and consequently moved to a more modest location at 649 Union in a diverse neighborhood just southeast of downtown. A two-story house built in 1907, it would serve as the home where Junior would live out some his most formative years as a youth.

The Fords resided at Union Avenue until the summer of 1930, when Jerry Sr., at this point finding success in running his own business (check "Ford Paint & Varnish" below), wanted a home to show his rising economic prosperity. The family spent that summer fixing up a house at 2163 Lake Drive, once again in East Grand Rapids. Jerry Ford, Jr., spent his senior year of high school on Lake Drive before moving on to college in Ann Arbor. The Ford’s journey from their small home on Madison Avenue toward the more upscale house on Lake Drive was a testament to the strong work ethic and honest values of his father, whose principles would remain a strong influence on Gerald R. Ford throughout his life.

The Ford household rules were straightforward, framed by parental expectations and grounded in firm principles. “Whatever happened, you were honest,” Ford would later write. “Dad and Mother had three rules: Tell the truth, work hard, and come to dinner on time. Woe to any of us who violated those rules.”

Junior remembered his father as someone he learned from “by the example he set in his own life.” Ford Sr. was, seemingly by universal acclaim, a very hard worker and a very good businessman. And so it was in 1929 that he offered to purchase the paint manufacturing division from his employer, the Grand Rapids Wood Finishing Company. An agreement was struck, and Gerald Ford went into partnership with Louis Schuman, Ford managing the business and Doc Schuman, a chemist, mixing paints and varnishes. They opened their business, Ford Paint & Varnish Company, on the corner of Crosby and Elizabeth streets.

Within a few weeks the Stock Market crashed, and America slipped into the Great Depression. Ford’s reputation in the paint business did much to save the fledgling company. “Don’t stop placing orders,” his suppliers told him. “Your credit is good. If you can’t pay, we’ll work something out. But don’t stop buying.”

His virtue also contributed. Ford told his employees, about 10 people, he would have to reduce their pay and that his pay would be reduced to the same level. When business turned around, he would make up the difference. No one lost his job.

Junior and his brothers worked on the production floor alongside the laborers, pushing heavy tubs of paint over the rough floor and mixing ingredients. It was a hot and messy job for which they were paid about half the rate of full-time employees.

“Jerry had a reputation of being the sloppiest guy there,” his brother, Tom, recounted. But it was the reputation of his father that instructed the son. “Whatever he got into, (Dad) was highly regarded. He was really one hell of a guy,” reminisced Gerald Ford, Jr.

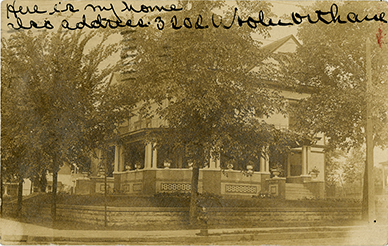

716 Madison Avenue

The earliest place that Gerald Ford called home was at 716 Madison Avenue. The house was rented and split in two, between the addresses 716 and 718, with his paternal grandmother and aunt occupying the other half. It was a neighborhood mixed with middle-class and working class families. Junior was an only child through much of his time at Madison Avenue, and his father was earning enough to take the new family on vacation to places like Florida. It was here that young Junior would play with other children in the neighborhood; though they were generally much older, he could hold his own, as he was already of a size and temperment that would make him an excellent football player. He would accompany his father to the YMCA, where he learned to be a terrific swimmer. On Sundays, the family would attend St. Mark’s Episcopal Church on Division Avenue. All in all, it was a good place to experience childhood.

In 1918, Junior Ford enrolled in Kindergarten at Madison Elementary, across the street from his duplex home. Kindergarten is taken for granted today, but at the time, it was a progressive idea that many schools across the country were just beginning to adopt. Junior enjoyed his time at Madison, which he attended through 6th grade.

"I’ll never forget one aspect of it,” he recalled of the school. “It was on the corner of Madison and Franklin Street, and there was a fire engine house right on the corner with the last horse-drawn steam engine. And when a fire broke out, those horses and that steam engine would come out hell bent for election! It was a thrilling sight!

As Junior Ford made his way through the early years of elementary school, it became apparent that he had a stutter. It was also discovered in the first grade that Junior wrote better with his left hand than with his right. After an attempt to make him write right-handed, which was common for the time, his teachers and parents gave up and allowed him to use his left hand. Consequently, his stutter began to disappear. For the rest of his life, curiously, Ford was right-handed standing up but left-handed sitting down.

At this point, Jerry Sr. was working for Heystek and Canfield, a business specializing in home decorating products like paint and wood varnish. He had previously been a traveling salesman for the company, but now thirty years old in 1920, Jerry had earned a managerial position. The Madison Avenue home began to look smaller with the birth of Junior’s half-brother, Thomas, just a day after Junior’s birthday in 1918. The higher manager’s salary earned by Jerry Sr. allowed them to take a step up in society and find a more suitable home. Having outgrown the working-class neighborhood around Madison Avenue, the Ford clan looked to own a home for the first time, setting their sights on the up and coming East Grand Rapids suburb. In East Grand Rapids, houses were newer, the neighbors wealthier, and it had an amusement park, Ramona Park (Check Ramona Park below), at Reed’s Lake. Constructed by the cable car company, the park was a staple of Grand Rapids entertainment for decades.

Money was put down to build a house on Rosewood Avenue. In 1922, the family left their Madison Avenue home behind to take up residence in the new, socially upward neighborhood. However, economic misfortunte would soon find the Ford family, and their time on Rosewood Avenue would not last long. Jerry Sr. lost his job at Heysteck and Canfield and was forced to sell his newly built home. The Fords moved to 649 Union, not far from where they started at Madison Avenue.

We had an amusement park in Grand Rapids called Ramona Park. It was at the end of the streetcar line. It had an old theater, had all kinds of concessions. They had numerous little Coca Cola stands. They had a roller coaster. They had all the things an amusement park had. Through a friend of mine at South High I got a job working out there for Alex DeMar moving supplies from one eating place to another. I would work there Saturdays and Sundays. I forgot how much I made – probably $3 a day plus what I ate. But that friendship had a curious long history. I worked hard. Alex liked me. He was probably 15 years older, a leader in the Greek community.

Gerald Ford

Ramona Park is fondly remembered by many in Grand Rapids. From the turn of the 20th century and for 10 years after World War II, the park offered visitors the thrill of bumper cars, roller skating, a fun house crowded with fake doors, rides on the Derby Racer rollercoaster, dance bands, sporting events, and more.

Reed's Lake at Ramona Park postcard, courtesy of the Grand Rapids Public Library

One of the attractions occasionally offered was dancing by ladies in dress somewhat risqué for the post-Victorian mid-west. The story is told that one summer day, when Jerry and his co-worker had a full day’s work before them, Jerry’s companion slipped off to watch the dance line, leaving Jerry to lug the crates of Coke and food to the drink and food stands. When Mr. DeMar stopped by, he found Jerry sweating at his job and the other boy distracted by silk stockings and lace. As some recall, Jerry’s shift of solo labor was completed without complaint.

649 Union Avenue

After a change in management at Heysteck and Canfield, Jerry Sr. lost his job, and though he quickly found a new position with a different company, he was no longer able to keep up with the mortgage to pay for the house on Rosewood Avenue. Forced to move, they found a house on the edge of the Hill District, at 649 Union Avenue. It was here where his two other half brothers were born: Richard was born in 1924 and James in 1927. When they moved to Union, Gerald Ford was almost ten years old and entering the 4th grade. He would spend the most formative years of his childhood at this address.

The neighborhood around Union Avenue was a mix of occupations and ethnicities, from the top end of the working class to the lower levels of the middle class. Half of the families were of Dutch origin, the most prominent ethnicity in the Grand Rapids area. The house itself was a two-and-a-half story structure with a large front porch and a two-story garage. It had the basic amenities of a pre-World War I home: a coal furnace, a bathroom with a toilet, sink, and tub, and a single telephone. A primary sign that the Fords were a middle class family was that they often hired household help, even if money was scarce. It was not a home of luxury, but 649 Union Avenue was an average middle-class dwelling for the times.

One of Junior’s many chores was to tend to the furnace, which required daily cleaning and refilling of coal on a daily basis. It was a task that required practice, as the coal had to be distributed in the furnace in such a way that it burned constantly throughout the night. This chore and others fell to Junior because his father’s new sales job at the Grand Rapids Wood Finishing Company kept him on the road for most of the week. As a consequence, Jerry Ford Jr. was often the man of the house.

Gerald R. Ford Jr., at age 10, on the front walk of 649 Union.

Gerald R. Ford Jr., at age 10, on the front walk of 649 Union.

Young Ford made many friends in the neighborhood, playing unorganized contests of football or baseball with other boys. When he was not engaged with chores or outside playing with friends, which was much of the time, Junior would occasionally pick up a book to read. He enjoyed the Horatio Alger books given to him by his father, as well as tales of King Arthur, but more often than not, he would have rather been outside playing sports. Sometimes, he played poker with friends. Every once and awhile, though, Jerry Sr. would find his stepson during these card games. Junior recalled:

In the back of our house, we had a two-story garage. Well, that pretty soon became the place where the Ingle twins (neighbors and close friends) and Pat Lusk, Ed Furch, myself, and some others had a club up there. I forget the name of the club, but we got on a binge of playing poker. I remember a couple of times when my stepfather or one of the parents of the other boys caught us, and we were pretty severely reprimanded.

It was on Union Avenue, during his elementary school years, where he learned to control what was becoming a prodigious temper. As his parents did not believe in physical punishment, Junior’s temper tantrums were dealt with by Jerry and Dorothy Ford in creative ways. His mother would point out how ridiculous he looked when he was angry, or simply confine him to his room. After one such tantrum, she made him memorize “If,” a poem by Rudyard Kipling. “It will help you control that temper of yours,” she told Junior. His father, on the other hand, would give him stern motivational talks. Overall, though, little discipline was needed, for Junior Ford was generally a cooperative youth.

The future president would call 649 Union his home until the last year of high school. However, before Jerry’s senior year in 1930, his father’s business prospects were on the rise. Jerry Ford Sr. wanted a house to better show his position as the head of the newly minted Ford Paint and Varnish Company. so he put money down on a large house in East Grand Rapids, at 2163 Lake Drive. Once again, the Ford family changed homes.

2163 Lake Drive

The Ford family moved to 2163 Lake Drive after a chain of events that led to Jerry Ford becoming the owner of his very own business. Sales of furniture, Grand Rapids' major export, had begun to drop throughout the 1920s, and companies started to branch out from their primary products. The company that Ford worked for, the Grand Rapids Wood Finishing Company, was doing just that. With dreams of financial independence, Ford had instilled enough confidence in his sales abilities that his boss, Albert Simpson, opened up an interior paints division and put Jerry Sr. in charge of the new operation in 1928. Carl Schumann, a chemist with a few paint patents to his name, was made technical director, and with Simpson looking towards retirement, the operation was spun off into its own separate company as Ford Paint and Varnish. It was ready for business in October 1929.

Despite the downward turn in the economy following the stock market crash, the company was establishing itself, and Jerry Ford Sr. wanted a house that would be fitting for a man who was his own boss. In the summer of 1930, he found a pre-war house in East Grand Rapids. It was in need of repairs, but it was large and the location was right. He put money down on 2163 Lake Drive, and every weekend that summer, Jerry Sr. and his sons worked to fix up the newly purchased home. The Ford family moved into the new residence that September.

Moving to East Grand Rapids brought up the issue of how Jerry Ford Jr. was to continue his enrollment at South High. The suburb had a school of its own, but, as captain of the football team, Jerry felt he had an obligation to finish with his present team. Having received permission from the city school district to remain at South, the next task was to figure out how to make the three mile commute from his new home. The summer before his senior year, Jerry worked three jobs: one working ticket stands at Ramona Park, one filling paint cans for his father’s business, and another flipping burgers and working the register at Bill’s Place. By the time school started, the seventy-five dollars he had saved was enough to buy an old 1924 Ford coupe.

Though the car got him through football season, it would not last the winter. On a cold and snowy night in December, Ford arrived home from basketball practice. Noticing steam rising from under the hood, he opened it up and saw that the engine was glowing red and then remembered he had neglected to put antifreeze in the radiator. It was common practice to drape blankets over the hood on cold nights to prevent the engine from freezing, so Jerry went a step further and put a blanket around the engine itself. Less than an hour later, as the Ford family was eating dinner, they heard sirens just outside the house. Rushing to see what the matter was, they saw that Jerry’s car was ablaze, It was too late for the fire department to save the vehicle. What made matters worse was that Junior had not taken insurance out on the car—he commuted by streetcar for the remainder of his senior year.

The Ford family was not on Lake Drive for long, taking up residence at 1011 Santa Cruz Drive in 1933. But by then, Jerry had left Grand Rapids, his athletic and academic careers taking him to the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor.

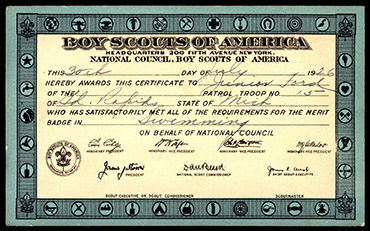

[My parents] urged me to join Boy Scouts as soon as I was old enough. We didn’t have Cub Scouts, so when I was 12, I and about five others my age in the neighborhood all joined Boy Scouts – Troop 15, Trinity Methodist Church…My parents strongly supported my Scouting. My stepfather was on the Troop Council, went to the Boy Scout camp my first year for two weeks. And for the next three or four years I worked as a non-paid aide or assistant.

-Gerald Ford

The Ford's were involved with several organizations aimed at improving the community. In addition to being a dutiful church-going family and members of the South High Parent Teachers association, Gerald Ford Sr. was involved in the Youth Commonwealth, an organization he helped create to help provide support for young boys in poor families. He was also a dedicated member of the Masons. Dorothy was involved with her organizations as well, such as the Santa Claus Girls, a group of women who would make or collect gifts to give to impoverished families of Grand Rapids. Junior, no doubt influenced by his parents’ engagement with the community, became involved with an up and coming organization called the Boy Scouts of America.

Jerry Jr. became eligible to join the organization on his twelfth birthday, and his scouting career began in December of 1925. He was sworn in by giving the Scout oath: “On my honor I will do my best to do my duty to God and my country and to obey the Scout Law; to help other people at all times; and to keep myself physically strong, mentally awake, and morally straight.” It was in Scouts where he learned an appreciation for nature, became a masterful swimmer, and gained experiences that he would take pride in for years to come. Ford would eventually become an Eagle Scout, the highest rank in the Boy Scouts, and remain connected to the organization and its ideals throughout his life.

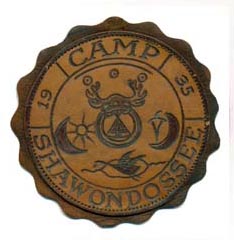

Camp Shawondossee

Jerry spent much of his scouting years at Camp Shawondossee, named for the spirit of the South Wind from the Song of Hiawatha. Located in a rustic wooded area near Lake Michigan, he attended the camp during the summers of 1926 and 1927, earning merit badges and making his way up the Scouting ranks. There were times when the remoteness of the camp proved dangerous, such as the time Ford had his tonsils removed:

The summer I became 15, I had to have my tonsils out. My doctor released me, I went to camp. Couple of days after the operation, and the first night up there, I began to hemorrhage. I didn’t know what to do. Finally, it stopped and I went to sleep. Camp Shawondossee… was about 30 miles from the nearest hospital. I was lucky.

He reached the final and highest rank of Eagle Scout on August 2, 1927, at the age of fourteen years old. The following year he returned to Shawondossee not as a camper, but as a staff member. It was around this time that he began to go by the name Jerry, like his step-father, rather than Junior, which can be gleaned from his merit badge records. As a staffer, he led the younger scouts and learned Indian dances with the other staffers for weekly pageants. Overall, Ford represented the model Scout, showing strong leadership qualities and being chosen to represent Troop 15 on trips to other locations. The summer of 1929 was Jerry’s last at Camp Shawondossee, but it no doubt had an indelible effect on his character throughout his life.

Mackinac Island

The First Eagle Scout Honor Guard at Fort Mackinac, August 1929. Ford is in the center.

The First Eagle Scout Honor Guard at Fort Mackinac, August 1929. Ford is in the center.

Towards the end of his staff tenure at Camp Shawondossee in the summer of 1929, Jerry Ford was offered the opportunity of his Scouting career. Earlier that year, a member of the Michigan state parks commission had the idea to install an “honor guard” at the historic fort at Mackinac Island, a small island situated between Lakes Huron and Michigan. This group would be comprised of the best Eagle Scouts the state had to offer, and their task would be to present the history of the fort to the visiting public. The Grand Rapids Boy Scout council named Jerry Ford as the city’s representative, and instead of going back home from camp to prepare for the coming football season, Jerry was sent to Lansing to meet with the seven other members of the honor guard and have a photograph taken with Governor Fred Green.

After an overnight voyage on a steamship, the Scouts found themselves on Mackinac, where they would remain through the month of August. They camped inside the fort and cooked their own meals, living primitively compared to the amenities visible less than a mile away at the lavish Grand Hotel. The Scouts gave daily tours of the fort, and fired the fort’s cannon with every sunset. With their time off, they were free to relax and explore the natural beauty of the island.

Ford, though, had brought a football along and was busy preparing for his senior year season. Jerry enjoyed his time at Mackinac Island, but his Scouting days were coming to an end, with his focus shifting towards the business of football and the pursuit of college.

The 1929 Eagle Scout honor guard inaugurated an enduring tradition, one that continues to this day.

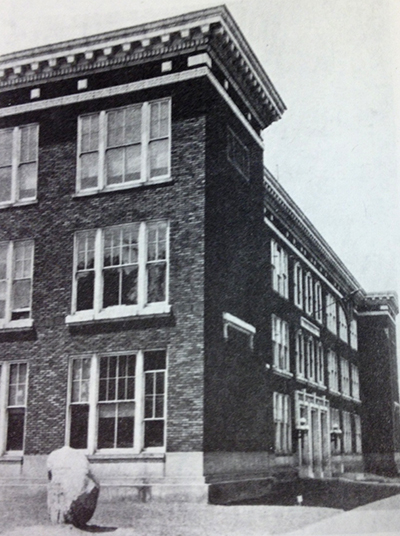

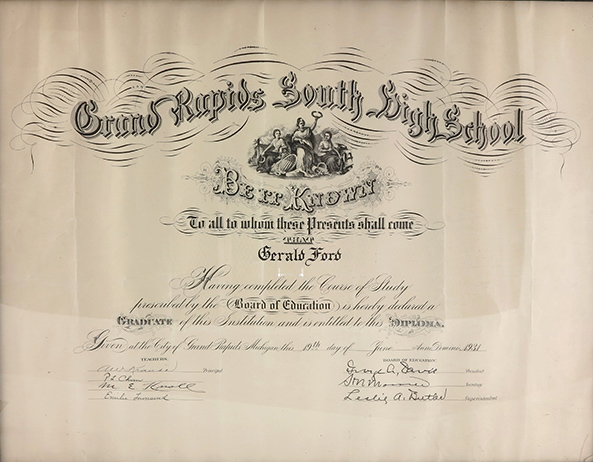

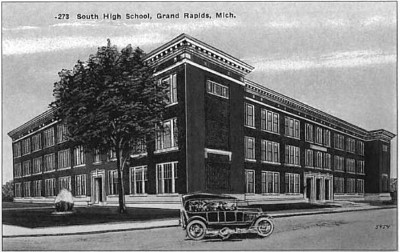

While in the sixth grade, Junior’s parents deliberated where he should attend high school. Back then, elementary schools ran through the sixth grade, and high school began the following year. School district lines converged on their block of Union Avenue, and there was a choice between three schools. Central High was a school geared towards the upper-middle class, and Ottawa Hills was a newer school catering towards the elite. South High, though, consisted of a more diverse collection of students; working class folks and minorities sent their children to South, as well as a few pockets of well-to-do families. The Fords sought help from family friend Ralph Conger, who was the athletic director at Central. “You send Junior to South,” was Conger’s advice. “That’s where he’ll learn more about living.” Jerry and Dorothy saw that South offered the greatest opportunity for their son, and the younger Ford began his high school career there in September 1925.

South High was a relatively new school, a three-story brick building constructed in 1915, and just a little more than a mile’s distance from the old Ford household on Union. Ford managed the early years of high school well enough, and at the end of eighth grade, he had reached the limit of compulsory education in the state of Michigan. His step-father had left school after the eighth grade to find a job, and he wanted Junior to have every opportunity to graduate from high school. It was at this point that Jerry Ford Jr. decided he was going to set his career track to that of a lawyer, which came as a surprise to his parents. There were no lawyers in the Ford family, and Junior was not a particularly gifted speaker. All the same, Junior began to take college-prep courses and joined the debate team to give him practice for his aspiring career.

Over the next four years, he became a football star, which made him a popular guy. He drew the interest of many girls in his class, but had few dates. Ford had very little time for a social life between schoolwork and sports. He worked several jobs on the side as well, assisting his step-father’s paint business and working concessions at Ramona Park.

He also had a job making hamburgers at a diner, Bill's Place, which was also the scene of a dramatic meeting (Check Bill's Place and Leslie King below) with his biological father, Leslie King. This was the first time that Jerry had ever met the man, and the meeting caused him much stress. After the meeting with King at the diner, though, Jerry did not encounter him again for several years.

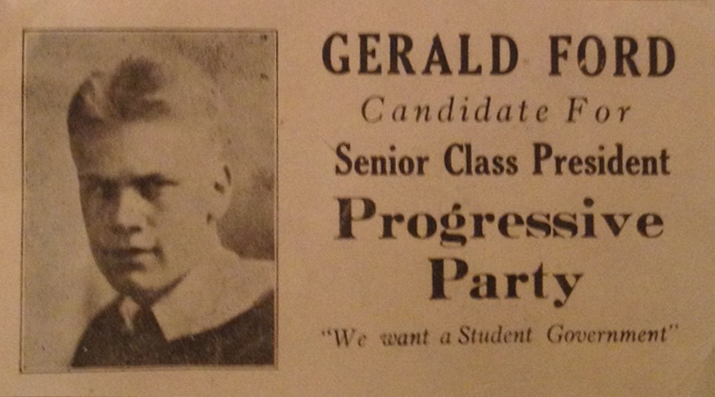

Ticket for Gerald Ford's Class President campaign.

Ticket for Gerald Ford's Class President campaign.

Despite his busy schedule, he ran for student council president his senior year, which was technically his first political campaign. By the time he entered the contest, another slate of candidates had already registered as Republicans, the favored party, and he opted instead for Teddy Roosevelt’s “Bull Moose” Progressive party. Ford’s leading opposition was William Schuling, also a popular senior. Jerry would find, however, that the deck was stacked against him in 1930.

His most daunting opponents were his own coaches. “(Ford) was out for three sports, and the coaches couldn’t see him directing a Student Council meeting when the teams were practicing,” his football coach, Mr. Gettings, explained. “I had physical education classes, and I told the boys in the class to vote for Bill Schuling because we needed Jerry out for football and basketball and track. So the Coaches campaigned against him and Bill Schuling won. It wasn’t (Jerry’s) fault because the coaches ganged up on him.”

In the spring of 1931, a theater offered a contest to select the city’s most popular senior. The Majestic Theater was a downtown fixture, a three-story vaudeville and movie house that seated 1,200 patrons. Feeling the sting of having lost the Student Council election, he was determined to win this new challenge. The voting extended through the month of March, and Junior would take his brother, Tom, downtown to pick up discarded ballots. “It was the only time he stuffed the ballot box,” Tom recalled. But Ford was not alone in this practice. “My problem was the other guys had their people in there, too,” Tom said. With Tom’s help and the help of others, Junior won the election, garnering over 1,000 votes. In June he received his reward when he joined winners of similar contests from other cities to make an all-expenses-paid trip by rail to Washington, D.C. This was Ford’s first trip to the nation’s capital, where he enjoyed a week of sightseeing.

Upon finishing high school, he had his sights set on college, and football was key to his collegiate opportunities. He had considered several schools, but the University of Michigan stood out as the best fit. He received help from Principal Arthur Krause, who started a scholarship for Ford, and well as from family and friends. Michigan football coach Harry Kipke courted the star South High center, securing Jerry a job waiting on tables to pay for meals. “Many people helped me,” Ford reflected, “but football was my ticket to college. That’s the only way I got to Michigan, and that was the luckiest break I ever had.”

Bill Skougis owned a small diner near the high school, and Ford worked there throughout his time as a high school football star:

“There was a little restaurant across from the high school. Bill Skougis, who ran this hamburger stand, always hired football stars. My sophomore year, when I played well, he offered me a job. He had about four of us, maybe five, working, for which we got paid $2 a week plus lunch. But he limited us to 60 cents worth of lunch. We had to work one night a week from 6 to 10. My job was to work at the counter, washing dishes and making hamburgers. And when people left and paid their bill, I had to handle that part of the job.”

In 1930, when Jerry was sixteen, an unexpected patron walked through the doors of Bill’s Place during a lull after the lunchtime hour. A large, well-dressed man approached the counter and addressed Ford.

“Are you Leslie King?”

“No,” replied Jerry.

“Are you Jerry Ford?”

“Yes.”

“You’re Leslie King. I’m your father. You don’t know me. I’d like to take you to lunch.”

Jerry had remembered that when he was about thirteen years old, his mother had told him of her previous marriage to a man named King, but he did not see why any of that would matter at the present moment.

“I’m working,” was Jerry’s reply.

“Ask your boss if you can get off.”

Jerry told Bill that he was having a personal crisis and that he had to go to lunch with this person. Bill consented, and Jerry left the restaurant with Leslie King. Outside of the diner was parked a nice car with a woman sitting in the front seat who King introduced as his wife. They had a meal at the Cherie Inn, where King explained how he had found Jerry. He was passing through the city; he had picked up a new car in Detroit and was en route to Wyoming. He knew he had a son who went by the name Ford and was currently attending high school in Grand Rapids. He was going to go to every high school to ask for him, but he had guessed South correctly on the first try, and they told him that he was working at Bill’s place.

Jerry remembered much of the conversation to be “superficial,” and conversed with King to be courteous. “It was a hell of a shock for a sixteen-year-old kid,” Ford recalled. “I was not frightened by him but by what I was going to tell my parents that night. And I was really terrified about that. He meant nothing to me.” After lunch, King took his biological son back to Bill’s place and handed him a twenty-dollar bill before departing. Jerry told his mother and step-father about the incident later that night, once his brothers were in bed, and his mother told him the entire truth about her previous marriage. Jerry’s fears proved unfounded, as his parents reassured him that they loved him, and told him to put the whole ordeal in the past.

The only other time anything took place between Jerry Ford, Jr. and Leslie King was when the former, needing cash to continue his college education, wrote his biological father for financial help. The letter was ignored. Years later, Dorothy Ford successfully sued her ex-husband for the child support payments that had not been paid. King passed away in Arizona in 1941.

Academics

Gerald Ford, Jr. was part of the 14th class to graduate from South High, one of 232 seniors photographed for the 1931 high school yearbook. His reputation was made as an athlete, the tenth of South High’s hundreds of athletes to be named All-State. But Junior was as competitive a scholar as he was an athlete.

Though he was an average student in English and Latin (he particularly struggled with the latter), Jerry was an excellent student of history. Virginia Berry remembered attending the same history class with Jerry. “Our teacher gave weekly exams and the way it went was one week I would get a ninety-six and Jerry a ninety-three, next week he’d get a ninety-seven and I’d get a ninety-four. I sat in the back of the room and Jerry up front, and every time exams were returned he would come back to ask what my grade was. He didn’t resent it if I got a better grade, he was just checking. We both got A’s in that subject, the only two.”

Allan Elliott was the quarterback of South High’s 1930 team. He and Ford were close friends. Elliott eventually would earn a doctorate in psychology. Later he explained, “Not many of us (classmates) harbored a thought of entering college, consequently most of us selected courses of study that would get us through high school. Not Jerry…. He selected the most difficult courses in a liberal-arts college-preparatory program…. What’s more, he was an honor-roll student all the way through high school, while participating in athletics, clubs, student council, and other student activities.”

Ford would make the Honor Society and finish in the upper tier of his graduating class. His teachers remembered him as a quiet yet attentive student. Marion Blanford, his history teacher, described him as “not a real outgoing” student, even “pensive.” “He was never egotistical, but always cooperative. He was an honest, decent sort of kid,” Blanford said. Ford recalled himself being “an excellent student in history and government. I was a pretty fair math student. I took chemistry and several other scientific subjects. I was never a very good student in that regard.”

Football at South High

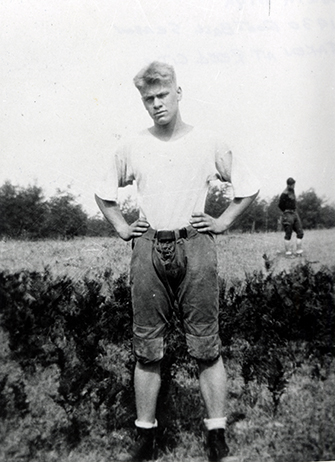

In the spring of Junior’s eighth grade year, over half of his class turned up to try out for the “second team” football squad that would be assembled the next fall. So popular was the sport that any boy who had a trace of athletic ability would try out for the chance of being on the team, and as a result, popular at school. South High football coach Cliff Gettings, himself a young man a few years out of college, was an imposing presence among these eighth graders. He saw Ford, with his bright blonde hair, and sized him up as a lineman. “Hey, Whitey, you’re a center!” he yelled. It was a designation that would stick through the duration of Jerry’s football career. He impressed at the tryout and easily made the freshman team, coached by “Pop” Churm (see below), who would serve as an advisor to Jerry through high school.

After making the second team for his freshman year, Junior, who was called “Junie” by his teammates, was always looking for opportunities to practice. Center was a much more complex position in those days, when football was still a primitive version of what it is today. “You had to perfect different types of snaps,” Ford recalled. From his coaches, he had to learn “how to snap the ball back, leading a tailback a step in the direction he was going to run, putting it high and soft for a fullback coming into the line, getting it on the right hip for the punter. And then after you centered the ball, you had to be quick to block the opposing lineman who had the jump on you.”

Junie excelled at the game in every way, thoroughly enjoying the team effort and individual aggressiveness that football requires. In fact, he began to develop a reputation as a hothead, delivering hits that drew penalties and the occasional ejection. His old temper was flaring up on the field, but by his senior year, he had learned to control his anger during games.

Ford, as well as being a quality player, acted as an informal leader to the freshman team, and he landed a varsity spot as the backup center for his sophomore year. However, the first string center, Orris Burghdorf, was injured before the season began, giving Jerry the opportunity to start a few games. By the time Burghdorf had recovered, Ford had proven himself to be a starter, and it was where he remained through his senior year.

Once on the varsity team, the crowds were larger and games were written up in the city papers. Jerry, though, simply concentrated on winning the contests at hand, blocking out the distractions that came with being a high school football star and all-city player. Three weeks into his junior year, though, his football career hung in the balance when he hurt his knee. With little improvement as the season wore on, he was missing games, but through an acquaintance with Danny Rose, a teacher at South High and a former Michigan basketball star, it was arranged to have surgery in Ann Arbor to repair the floating mensicus in his knee. The operation was successful, and Ford was ready to succeed in his final high school season.

The 1930 season, Ford’s senior year, was a pinnacle of his football career. The squad was a winning team and came to be known as the 30/30 Club (see below). The season was highlighted by the all-city game (see below), the final contest of the season played against the formidable Union High team. After an arduous struggle marred by blizzard conditions, the game ended in a scoreless tie. Jerry's high school career was over, but he would move on to larger crowds and greater recognition as the eventual starting center at the University of Michigan.

The story is told that when he was principal of Alpena High School, students played a joke on him by placing a baby in his lap and calling him “Pop.” He liked the sound of it and played along. Afterward, he was seldom called anything else.

Churm learned from another teacher that Grand Rapids soon would be opening a new high school on the corner of Hall and Jefferson. He applied to become its athletic director and was hired. When South High opened in 1915, Pop Churm was its football, basketball, track, and cross country coach. Eventually, he would hire others to coach football and basketball, but Churm would continue to coach track, the sport he loved best.

Along the way, Churm also taught American history and government, and served as senior class advisor. In 1928, Churm added a new member to his track team, Junior Ford. The team would win city championships each of Ford’s four years. And Churm would be coach, teacher, and advisor to Junior through his high school years.

“Jerry was always honest and dependable,” Pop Churm recounted. “He was quiet and everybody always liked him. He wasn’t ever selfish, and he isn’t vain at all.” Reflecting on Ford’s success, Churm said, “It just goes to show that if you have character and decency and honesty, you’ll get ahead.”

Pop Churm served at South High until 1953, when he retired. He died in 1978, aged 91. President Ford remembered him as “…the very best. Pop was loved, respected, and followed because he always stood tall and strong for what was right. He epitomized character, compassion, leadership and patriotism.”

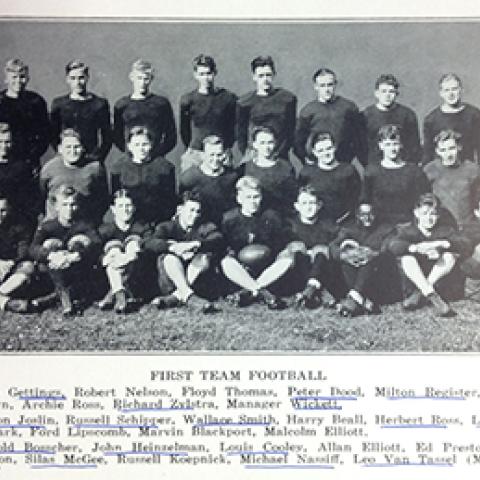

The 1930 South High football squad was special. Junie, the team's All-City center, captained the team, and was destined to be named All-State. Ford snapped the ball to quarterback Allan Elliott. “He was Jerry’s best friend and the two of them worked beautifully together,” recalled Clifford Gettings, South High’s head football coach.

Elliot said that Ford’s character showed itself early on, “…as early as the ninth-grade football season when a group of us played second-team football and recognized him as the person that we could turn to for leadership.”

Junior showed that leadership before his senior season began. The 1929 team opened its season with a loss on the road to Ottawa, by a 10 – 6 score. The 1930 season would open with South hosting Ottawa, a team stacked with veteran players. Ford thought the 1929 squad began the season out of shape and was determined not to repeat that error in 1930.

Coach Gettings remembered that Junior “…took the group up to his dad’s cabin … about a week before practice started. Did they get into condition! They were in shape for Ottawa and beat them 18 – 6.”

South would not lose that season and would be crowned state champions. In 1931, tackle Art Brown and halfback Dick Zylstra organized a breakfast at a local hotel for Thanksgiving morning, the same day the previous year that witnessed the epic battle between South and Union. The breakfast became an annual tradition. Eventually, they began referring to their group as the 30/30 club – the thirty members of the 1930 team. Ford missed a few of the meetings during World War II and while traveling as a Congressman. But the 44th meeting of the 30/30 Club was held in the White House, hosted by President Ford.

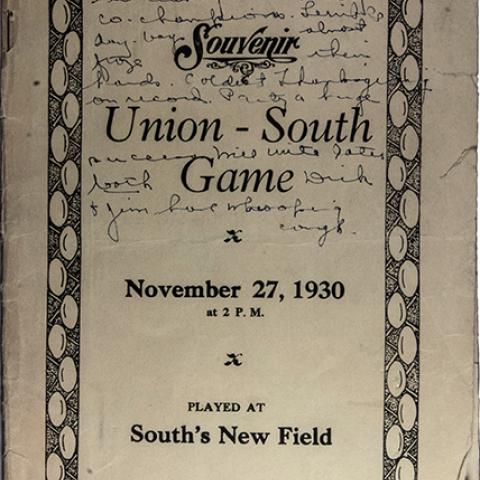

The 1930 season came down to the last game of the season. The city championship was on the line and with it a chance to become state champions. Both Union High and South High offered undefeated teams. South welcomed the visitors to its new athletic field, where Principal Krause urged each team to “Let good sportsmanship mark this encounter to the extent that the winner will be modest in victory, and the loser gracious in defeat.”

Neither team would have opportunity to test those qualities. A blizzard swept through Grand Rapids, and on Thanksgiving Day the temperatures plummeted. Ford remembered the crowds and the effort to clear the snow. “That high school game drew 12,000 people. They got all the equipment out and cleared the field. The snow was piled up high on the sidelines.” Art Brown recalled that “…it was the first game in the city of Grand Rapids that they charged a dollar admittance.”

The game was marred by fumbles and stalled drives as players slogged through ankle-deep snow and mud. Each team had opportunities to score, but neither did. And just as had happened when the two teams first met in 1916, the game ended in a scoreless tie. Writers and fans lamented the way weather affected the performance of two powerhouse teams and that the tie ended the hopes of either team winning the state championship. Together, however, Union and South would be crowned co-champions of Grand Rapids. And fans left South field knowing they had seen an epic contest.

Later it was learned that Union had played an ineligible student and had to forfeit many of its 1930 games, including the South contest. South then was named city and state champions for that year.

Other Sports at South High

The 1931 Grand Rapids YMCA swim team. Ford is in the front row at far left.

The 1931 Grand Rapids YMCA swim team. Ford is in the front row at far left.

Jerry Ford, while known for his football exploits, was a well-rounded athlete during his high school years. He also competed in track, basketball, and swimming. Danny Rose, the South High physical education teacher who had helped Ford receive a knee operation during the spring of his senior year, was also the basketball coach. To repay Rose for his help, Ford joined the team following football season his senior year. He was not an especially talented offensive player, but was an asset on defense. “[Rose] would kid me about my lack of production on field goals,” Ford later wrote, “but praise me for holding down the scoring of the other team’s best shooter.”

Jerry had learned to swim at a very young age from summers spent at Ottawa Beach on Lake Michigan with his family, and he swam competitively with the YMCA team during the spring of his senior year. Simultaneously, he was on the South High track team, attending meets all over the state. These were his last athletic experiences of his high school career. “Athletics, my parents kept saying, built a boy’s character,” Ford recalled in his memoir, and he took that advice to heart as a youth.

The University of Michigan

Jerry Ford's senior year Michiganensian yearbook Hall of Fame entry, 1934. Courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library.

Jerry Ford's senior year Michiganensian yearbook Hall of Fame entry, 1934. Courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library.

Ford was strapped for cash for the entirety of his collegiate career, but he made ends meet with the help of many friends. The 1930-31 academic handbook informed students that their first year would cost an estimated $833. This figured included $98 for tuition, $490 for room and board, and $150 for incidental expenses. This posed a problem for Ford and his family. His step-father's paint business was struggling through the Depression, so Jerry would have to look elsewhere for financial aid.

His high school principal pledged his support early on. “[Principal] Krause came to me one day,” Ford recalled, “and said, ‘Tuition at the university is $100 a year, and I know your Dad doesn’t have that. And I know you can work this summer for him at forty cents an hour. But that’s not going to give you much money to go to Ann Arbor. You know, we have a book store at South. And I think we ought to start a scholarship with the profits. I think we’ll make the first award to Jerry Ford.’ And that’s how I got my tuition,” Ford recalled.

Others helped as well. Michigan football coach Harry Kipke made sure Ford had a job awaiting him on campus. A few times a semester he sold his blood for $25 a pint to the University Hospital. Another source of income came from his dad’s sister, Aunt Rua, and her husband, Roy Laforge. Each was in sales, and together the couple was childless. They pledged weekly support. “Every Monday I got a $2 check, and that was my spending money.”

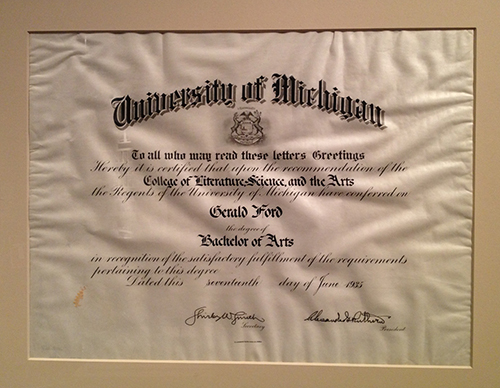

Funds would always be tight, but Jerry made the most of his college experience. He studied economics and political science with good marks, and had a standout career at the center position for the football team. He became involved with Greek life during the spring of his freshman year, and made friends that would remain in his life for years to come. In his senior year, he was selected as a member of Michigamua, one of the school's honor societies. All in all, Jerry's undergraduate years were marked by success and prestige.

College Academics

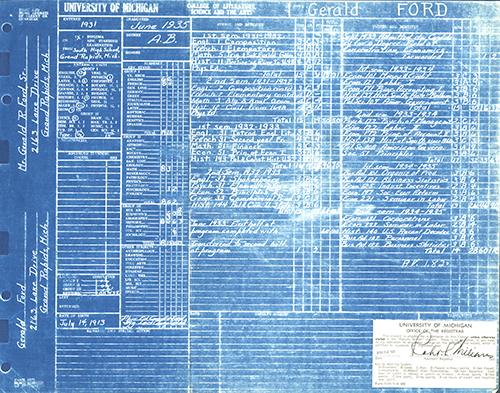

Ford's college transcript, scan courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library

Ford's college transcript, scan courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library

Jerry Ford studied economics at the University of Michigan, taking 33 hours of coursework. He also completed 23 hours of study in history, mostly in American political history. Finally, Ford added 12 hours of business administration and six hours of political science. Ford finished with 120 hours of classroom instruction, earning a B average.

His freshman year was crowded with 30 hours of English, French, math, and history. Geometry, trigonometry, and Western Civilization presented him with few problems. Second semester French, however, brought him his first (and last) D. Ford carried 31 hours his sophomore year, where he studied the fundamentals of economics and the formation of the US constitution.

In his junior year, Ford concentrated on economics, taking 15 hours of courses that reviewed banking history, the challenges of wage earners, and the fundamentals of double-entry accounting. He also studied the history of the American South and American government, both national and state.

Ford loaded his senior year with economic courses in industrial relations, wages, and the economic doctrines of radical and conservative political systems. He also studied the organization of corporations and took basic business courses along with a course in recent US history.

Fraternity Life

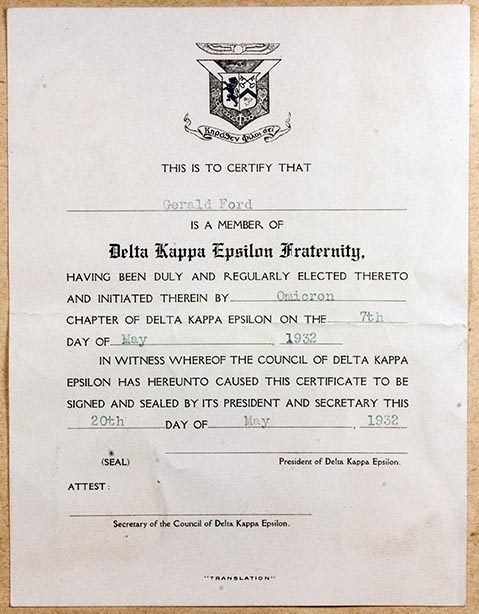

Ford's Delta Kappa Epsilon certificate of membership

Ford's Delta Kappa Epsilon certificate of membership

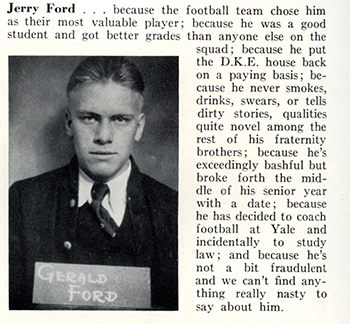

Delta Kappa Epsilon would never challenge any of the other fifty-five University of Michigan fraternities for a scholastic trophy. Of the fifty-two that had been on campus longer than ten years, DKE ranked dead last for academic achievement when Jerry Ford pledged in March 1932. One frat brother later admitted Ford was added to the house in hopes he might raise the fraternity’s grade point average.

DKE was a social house with a reputation for partying. “It was a well deserved reputation,” Ford said. "Because I divided my time between studies, sports, and part-time jobs, I seldom had time for parties and I guess I was naive about alcohol." It was here that Jerry mixed for the first time with people of wealth, yet Ford struggled to finance his expenses. The DKE manager gave him a job washing dishes to help pay his board when Ford moved in at the start of his sophomore year.

At the frat house on 1912 Geddes, Ford roomed with Eddy Landwehr of Holland, Michigan; Chuck Greening from Monroe; Jack Beckwith, who would be the best man at Ford’s wedding and godfather to Ford’s first son; and David Conklin, whose Battle Creek football team lost to Ford’s South squad. Here he also befriended Phil Buchan, with whom Ford later would practice law, and John R. "Jack" Stiles, who would be his first campaign manager.

1935 Michiganensian photograph of the DKE fraternity. Ford is second from right in the front row.

1935 Michiganensian photograph of the DKE fraternity. Ford is second from right in the front row.

Ford’s three years with DKE did not heal the fraternity’s reputation, but it helped make Ford’s. When fraternity brothers could not balance the house’s books, they turned the red ledger over to Ford who put them in the black. The Michiganensian, Michigan’s yearbook, placed the senior from Grand Rapids in its Hall of Fame, in part “because he put the D.K.E. house back on a paying basis.”

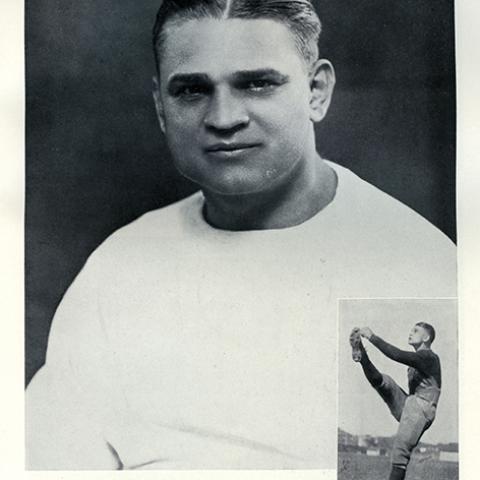

College Athletics

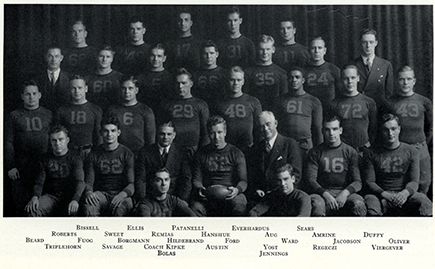

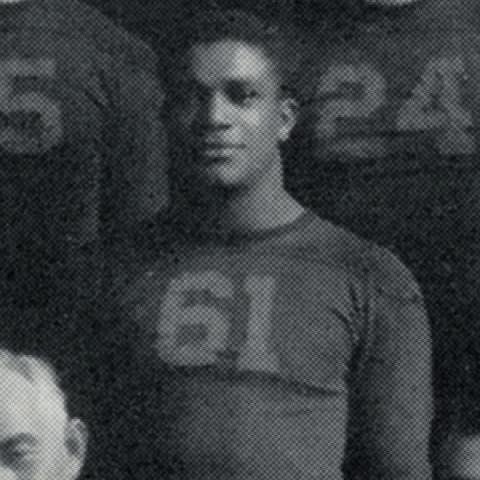

Photo of the 1934 Varsity squad from the Michiganensian

Photo of the 1934 Varsity squad from the Michiganensian

More than anything else, it was football that characterized Jerry’s time in college. The Michigan football program had a reputation for being one of the best in the nation, founded on an offensive strategy described as “a punt, a pass, and a prayer.” Ford described it as such:

The theory that [athletic director Fielding] had developed—and that coach Harry Kipke (see below) refined—was that if you had a good punter, a good passer and a strong defense, you would always win. If you won the toss of the coin, you always kicked off and gave the other team the ball. You counted on your defense to force them into mistakes. Inside your own 40-yard line, you always punted on second or third down. If you were near your own goal line, you punted on first down. If your punter did his job, you could pick up 10 or 15 yards with every exchange. Then, if your passer connected, you could score and score again.

In his first year, Ford won the Meyer Morton Most Promising Freshman trophy, an award for the most promising player on the freshman squad and cementing his reputation as a person of note on campus. However, Jerry saw little playing time during his sophomore and junior years, as his place as a starter was blocked by Chuck Bernard, an All-America center. “Not playing was tough,” Ford reflected, “but I learned a lot sitting on the bench. I learned that there was the potential always that somebody could be better than you, and Chuck was better overall.” In two tears as the second-string center, the Wolverines were undefeated and won two national championships.

Ford’s senior season began with promise. Key players like Chuck Bernard had graduated, but the team returned experience and talent. Many believed another conference title was attainable, if not a third national championship. Ford was determined to have a good year. Troubles set in, however, before the season’s first snap. Kipke’s offensive formula, “a punt, a pass, and a prayer,” was disrupted when his quarterback went down in practice and the punter was soon hurt.

“That last year,” Ford recounted, “we had an excellent passer named Bill Renner, who broke his leg before the season started. Our punter was the best I ever saw in pro or college, John Regeczi, and he got hurt in the third game. If your system depends on a punt, a pass, and a prayer, and all you have left is prayer – well, that might put you in good hands, but you better not count on any favors.”

The school that had not lost a game in two years would win but one game this season. The win against Georgia Tech (see below) was important symbolically, but it was a weak balm for a proud institution. The Michiganensian yearbook began a photo spread of the football season with these sour words, “When you read this book twenty five years from now, you will have forgotten the 1934 football season, we hope….”

Yet Ford remembered it fondly. “One of the greatest awards I ever got, that I prized most highly, was the fact that my teammates, my senior year, selected me most valuable player.” He would go on to other honors – All Star games and professional offers – still, his senior season notwithstanding, Michigan football had been very good to Jerry Ford, and he had been very good for it.

Harry Kipke was an athlete’s athlete. A star player for Lansing High School, Kipke took his talents to the University of Michigan in 1920. He was a three-year starter at half back and punter for head coach Fielding Yost, earning All-Conference honors twice and All-American honors once. He captained his senior team to an undefeated season, capped by being awarded 1924 National Championship honors. Along the way, Kipke earned letters each of his three years in football, baseball, and basketball, a feat accomplished by few athletes at that time.

Kipke coached baseball at the University of Missouri for a year and was head coach at Michigan State College in 1928. The next year he was named head coach at his alma mater by Yost, now Michigan’s athletic director. Kipke would coach the team to four straight conference championships and back-to-back national titles before resigning after the 1937 season. He finished with a 46-26-4 record.

Kipke not only found Ford his first job at the University Hospital, waiting on tables in the interns’ dining room and washing dishes in the nurses’ cafeteria, Coach Kipke also found Ford employment as he graduated. “In the spring of my senior year, Harry Kipke got me an assistant football coaching job at Yale University under head coach Ducky Pond. As assistant line coach, head Junior Varsity coach, and the man in charge of scouting our opponents from 1935 through 1940, I was able to attend and graduate from Yale University Law School.”

They first met on what was for both of them their first day in college. Long lines of students filed into Waterman Gymnasium to register for classes and pay tuition. Jerry Ford noticed the African-American Detroit athlete. “This chap came over to me and said, ‘I’m Jerry Ford. Aren’t you Willis Ward from Detroit?’” Ward recalled. There began a friendship that would stretch beyond the campus gridiron.

Ford and Ward toiled through their freshman year, competing for a chance to make the varsity team. Ward would become a backup right end to the great Ivy Williamson, captain of the 1932 squad, before becoming a starter his junior year. Ford would win the Most Promising Freshman award but would have to wait until his senior year to become starting center. It was in the third game of a disappointing senior campaign, however, where their stories fused. The previous year Athletic Director Fielding Yost struck a deal with Georgia Tech to play a game in Ann Arbor. As the 1934 game approached, the southern school insisted that Michigan not field its star right end. In an age of segregation, Tech forswore playing with or against African Americans. Yost agreed after wringing from Tech the concession that they would pull their star end, E. H. Gibson.

The campus erupted when the news leaked. Demonstrations were held, petitions were circulated, and threats to disrupt the game issued. Ford was angry and considered not playing. Looking for advice, he called his father, who said, “You have an obligation to the team and the school.” Ford thought he also had an obligation to Ward, whom he talked to next. “Willis urged me to help the team.”

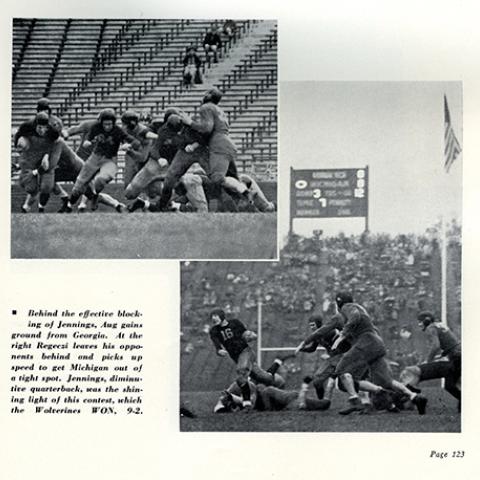

Ford centered the ball that Saturday on a field soaked by October rains.Gibson watched from the sidelines, and Ward watched from the press booth. Perhaps the rain dampened the crowd’s enthusiasm. Among the 30,000 spectators, no protests were made; the fight was confined to the gridiron. Punt followed punt that day, and dropped passes made advances rare. The score was tied at halftime when Michigan’s captain, Tom Austin, saw his day end by injury. Ford stepped in, and the campus newspaper reported that he “proved himself an aggressive leader when he took over.”

Shortly afterward, Georgia Tech was forced to punt once again.Michigan’s replacement quarterback, Ferris Jennings, returned the ball 68 yards for the game’s only touchdown. Michigan later would add a safety and leave the muddy field a 9-2 victor.Perhaps the team felt vindicated, but some believed that so much was given by the Wolverines on that Saturday that little was left for the remainder of the season.The team would win no more games and be outscored 98-12. In fact, the Georgia Tech game would be the last football game Gerald Ford would ever win.

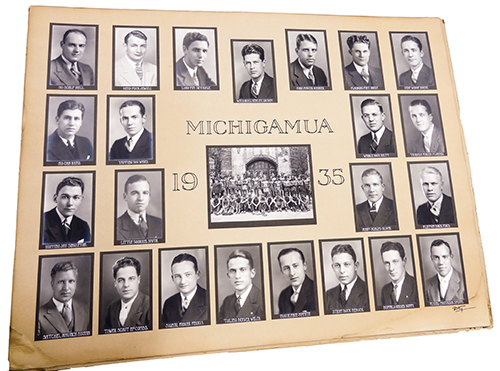

Michigamua

Michigamua Tribe of '35. Ford is the third row down on the far right column. Photo courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library

Michigamua Tribe of '35. Ford is the third row down on the far right column. Photo courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library

In a January 1935 letter to the Michigamua tribe, Dr. Harold Hulbert (tribe of ’14) wrote, “Congratulations to the Tribe and to Tapping and Ford.” With this line, he confirmed what the tribe had done in December 1934 by initiating through a special ceremony the University’s star football center, Jerry Ford, into Michigamua.

Using the tribe’s own terminology, Ford was elevated from “pale face” to “young buck” and was made a member of one of the University’s prestigious honor societies. The Michigamua Tribe met in the “Wigwam,” a room in the top of the Union’s tower. The room was adorned with animal skins and mounts, Native American artifacts, and outdoor gear.

The "Wigwam" in the Union. Photo courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library.

The "Wigwam" in the Union. Photo courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library.

Traditionally, the tribe selected about 25 second-semester Juniors whom they judged to be loyal and prominent students who would bring credit to the University. In the Spring semester those students would be “tapped,” or notified, of their selection and undergo initiation rites. Tribesmen were expected to undertake service projects that would benefit the University but that would bring the student no public credit.

Ford’s selection was unique, coming after the “Tribe of ‘35” already had been assembled. No reason is offered as to why he was invited as a late addition. But he was given his tribal name, “Flippum Back Ford” (because as a center, he flipped the football to the backfield), and he supported Michigamua’s efforts to find jobs for athletes and award letters to cheerleaders.

Campus Map

Gerald Ford graduated from the University of Michigan in the spring of 1935. After receiving, and declining, offers to play for several professional football teams, Jerry committed himself to working towards getting into law school, the path he had aimed for at the beginning of high school.

Initially desiring to attend law school in Ann Arbor, Ford found himself deeply in debt following graduation and would need a job to supplement any additional classes. He approached Harry Kipke about possibly working as an assistant coach for the football team. “Jerry,” he said, “I couldn’t pay you more than one hundred dollars.” Ford’s path to law school seemed blocked, but Kipke called him a month later and told him that Ducky Pond, the Yale head football coach, was in Ann Arbor to recruit an assistant. Lunch was arranged between Jerry and Pond, and the former received an invitation to New Haven to meet with other coaches.

Upon visiting, Ford liked the atmosphere of the Yale campus, and Pond offered him $2,400 to be an assistant line coach, with the catch that he also had to coach the boxing team in the winter. It was enough money to be able to pay off his debts and start saving for law school, so even though he had no experience with boxing, he could not possibly turn down the opportunity. He took a crash course at the Grand Rapids YMCA the summer before heading to New Haven. In the fall of 1935, he left Michigan behind to start a new chapter of life on the east coast.

Future Football Prospects

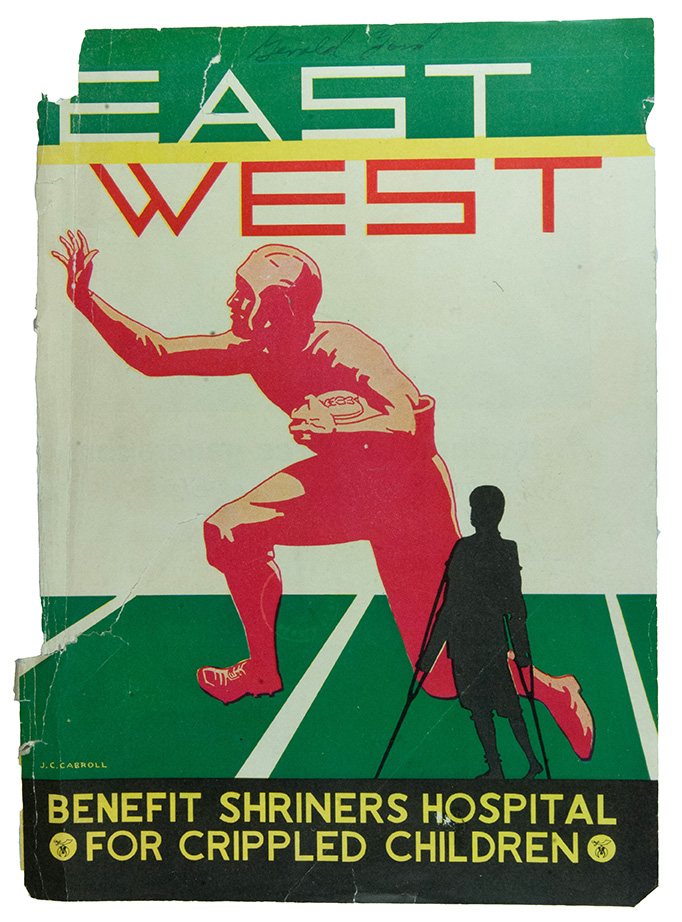

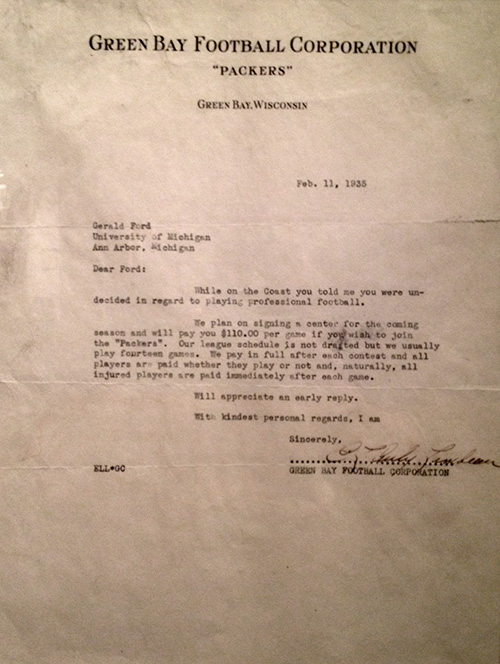

Following the final loss of the season against Northwestern University, Jerry was invited to play in the Shrine East-West charity game by the Northwestern coach. Ford recalled his invitation at the end of the 1934 season to attend the annual Shrine game in an article written years later for Sports Illustrated.

I was invited to play in the East-West Shrine Game in San Francisco on January 1, 1935, primarily on the recommendation of Dick Hanley, the Northwestern coach. I had had a pretty good day against his star guard, Rip Whalen. According to Hanley, when he asked Whalen why Michigan made so much ground up the middle that day, Whalen said, ‘Ford was the best blocking center I ever played against.’ I still cherish that remark.

The Shrine signed two centers for the East, a boy from Colgate named George Akerstrom, and me. On the train ride from Chicago to California, Curly Lambeau, the coach of the Packers, went from player to player, plying the good ones about their pro football interest. He ignored me. Then in the first two minutes of the game Akerstrom got hurt. I played the rest of the way – 58 minutes, offense and defense. After the game a group of us were given the option of a train ride home or a free trip to Los Angeles to see the movie studios. Being a conservative Midwesterner unacquainted with glamour, I naturally chose Hollywood. On the train from San Francisco to Los Angeles, Curly Lambeau sat with me the whole way. He suddenly knew my name. And he asked me to sign with the Packers. I told him I’d think about it.

The Packers offered Ford $110 dollars a game for fourteen games, while the Detroit Lions also offered the higher paycheck of $200 dollars per game. Jerry could have made good money playing pro football, but it would conflict with his primary goal: law school. He declined the offers and asked Harry Kipke if a coaching position was available at Michigan, with the ultimate goal of attending law school at Ann Arbor in mind. The funds were not available, but Kipke directed him to Ducky Pond, the head coach at Yale, who was looking for a line coach.

Ford was offered the position at Yale, and if he could not attend law school at Michigan, maybe there would be a way to make it work in New Haven.

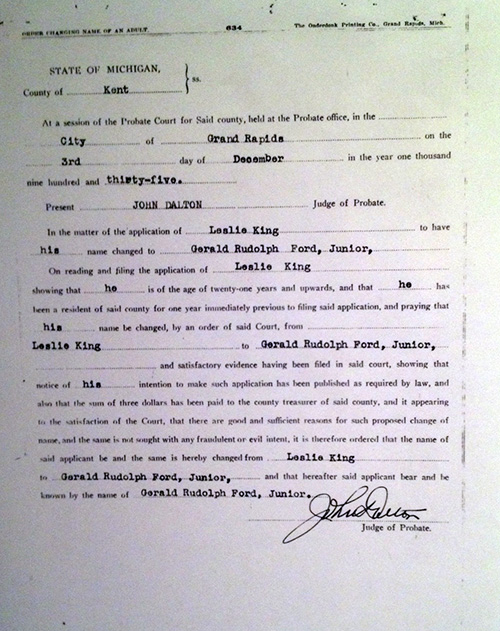

Taking the Ford Name

Gerald Ford, Jr. graduated from the University of Michigan in 1935. He had to borrow money to pay his final university bills, so that summer he worked at his father’s paint company while he received coaching lessons at the YMCA as he prepared for his job at Yale University.

Ford’s father was happy for the help. He had given Junior every advantage he knew to give – a loving husband to Junior’s mother, support in scouting and sports, an example of service to his community and church. Senior had also given the young man his name, that is, in every way but in the way the law recognized.

Now, as Junior faced leaving home for a vocation of his own, he placed an ad in the Cedar Springs Clipper newspaper:

Please to Take Notice that on Saturday, the 7th day of September, 1935, at ten o’clock in the forenoon, at the office of the Judge of Probate at the Court House in the city of Grand Rapids, County of Kent, Michigan, I will make application to the Honorable Judge of Probate in and for said County, to change my name from Leslie King to Gerald Rudolph Ford, Junior.

Signed, LESLIE KING

For perhaps the first, and certainly the last, time the boy who was born into that troubled Omaha house signed the name first given to him, in application to secure by legal means the name by which he was known to Grand Rapids, the name that was every bit as much his father’s (Gerald) and his family’s (Ford).

That November, just before Thanksgiving, he and his dad appeared before Judge John Dalton, who granted the son’s petition to take his father’s name. When Junior signed the petition, he did so using a name that the law now acknowledged was his own. But it had been his beginning as early as that February day in 1917, when Gerald Ford married Dorothy Gardner King and began by familial osmosis the process of transforming Leslie King, Junior into his own son. And in the transforming, Junior grew up grand, in every way that mattered to his mother and dad.

Yale University

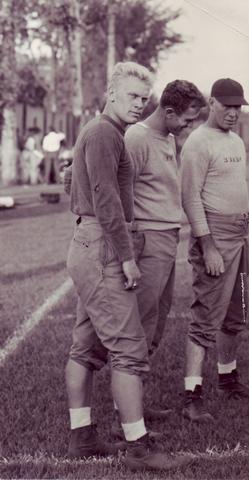

Coach Ford at Yale, photo courtesy of the Yale Office of Public Affairs and Communications

Coach Ford at Yale, photo courtesy of the Yale Office of Public Affairs and Communications

Reflecting upon his first impression of Yale, Jerry Ford was quite taken with the school in New Haven. “The Yale campus, an attractive place today, was even more beautiful then. The tall Gothic towers were inspiring, the long, sweeping lawns refreshing and clean. Everywhere I went, I discerned an atmosphere of scholarship, dignity, and tradition.” His job coaching the football team and boxing team was a full-time affair, leaving him no time to pursue dreams of a law degree, but he was soon able to pay off much of his college debt.

Ford enjoyed his coaching position, and it was job he did well. “I learned many things,” he recalled, “that you had to fit in with the direction and style of your boss. You carried out your duties with the individual players; you had to show them how to play and inspire them personally to play up to the limit of their capability. And you had to be a good representative of Yale University as you traveled around to go to alumni meetings and tried to recruit good players.”

Jerry continued to coach through the spring of 1937, and that summer he enrolled in a few law classes in Ann Arbor to test his ambition. He had been denied entry to Yale law school the following fall, and wanted to prove he was capable of completing the work. He received B’s in the two courses he took, and was allowed entry at the law school in New Haven on a part-time basis. He did this while maintaining his coaching duties, never mentioning to his superiors that he was also taking classes. Jerry managed the work load, and eventually received his degree in the spring of 1941. He returned to his hometown of Grand Rapids to practice law, set on the course that would lead him to the presidency.

Grand Rapids

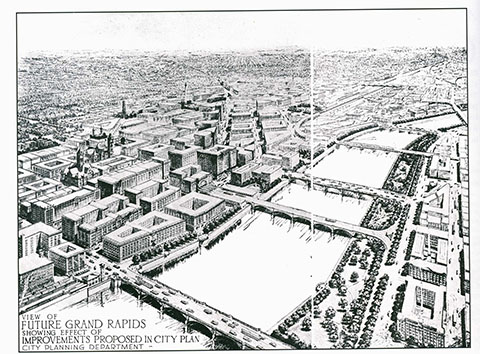

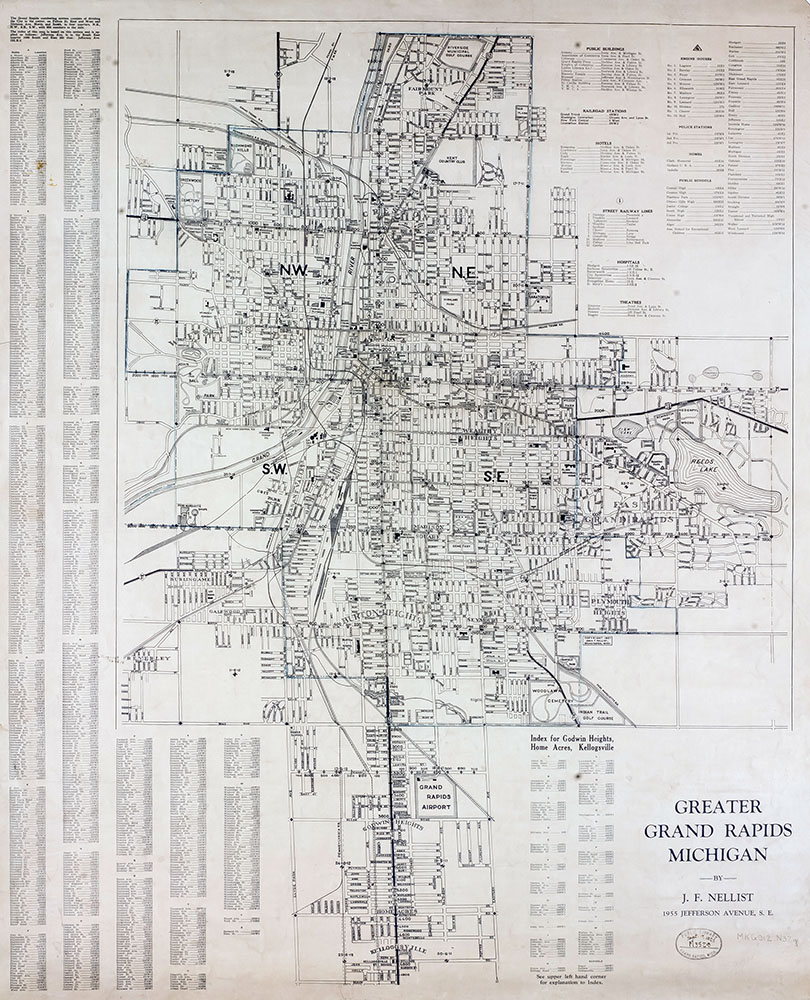

The city that developed Ford's character has a long history of work ethic, moral demeanor, and sense of community. Founded on the banks of the Grand River in 1838, the small fur trading village quickly grew into the largest urban center in Western Michigan.