“To understand him, you had to understand this; he wasn’t

human.”– Joe Dugan

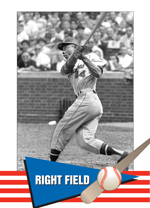

Babe Ruth

(1914-1935)

The Sultan of Swat

The very name of Babe Ruth conjures up images of towering home runs, stories of mythical proportions, and attributes that have become part of our language and culture. Yet the Babe was all that and more; in fact, he was himself Ruthian.

He was born George Herman Ruth, Jr., in Baltimore to lower class parents

who had a total of eight children, six of whom did not survive infancy. George,

Jr.’s childhood found him alone as his mother and father worked

long hours in a tavern. At age seven, his father took him to St.

Mary’s Industrial School for Children, and signed custody of George,

Jr. to the Catholic-run orphanage and reformatory. For the next

twelve years, the young George rarely saw his parents. Yet he

found a father figure in Brother Matthias, the Prefect of Discipline

for St. Mary’s, who took the child under his wing and taught him

the finer points of baseball.

Even

with the rising attraction of the Babe, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee sold

the young slugger to the New York Yankees prior to the 1920 season. It

was forever a dark moment for the Red Sox nation. Baseball’s

biggest star had come to the country’s biggest stage.

It

wasn’t long before Ruth’s talents were noticed by Baltimore

Oriole (a Boston Red Sox minor league team at the time) owner Jack Dunn,

who signed the teenager to a contract. When other players saw

the strapping young Ruth, they referred to him as Jack Dunn’s “newest

babe,” and Ruth was forever known as the Babe.

After only a few months with the Orioles, the Red Sox purchased the Babe’s contract and he became a pitching star for the Red Legs from 1915 to 1918. If Ruth had remained a pitcher, he might still have been a Hall of Famer, leading his team to World Series title in 1916 and 1918. His career earned run average in Series play is .87, a better mark than Sandy Koufax’s. Ruth pitched against the great Walter Johnson on six occasions, winning five.

What was catching everyone’s eye, however, were his skills as a batter. In just 95 games during the 1918 campaign, Ruth led the league in home runs; the following year he was placed in the everyday lineup as an outfielder, setting the record of most home runs in a season at 29.

Ruth clubbed 54 homers in

1920, almost doubling his record total from the year before and hitting

more than several teams. For perspective, someone today would have

to ring up some 140 homers in a single season to match Ruth’s feat. For

the next fourteen years, the Babe became the talk of baseball, leading

the Yankees to four World Series titles.

As big as he was on the field,

his late night exploits of partying and his mass consumption of beer

and hot dogs were also legendary. According to the Babe, he did

without so much as a youth that he couldn’t help himself. He

didn’t take care of himself but still put up numbers that boggle

the mind.

He holds the career slugging percentage mark and finished with the tenth highest batting average at .342. When he retired, he had hit more than twice as many home runs as the next person. In only 8,399 at bats, he slugged 714 home runs; had he as many at bats as Hank Aaron, he would have hit over 1,000.