“If Cool Papa had known about colleges or if colleges

had known about Cool Papa, Jesse Owens would have looked like he

was walking.” - Satchel Paige

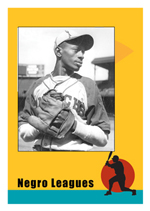

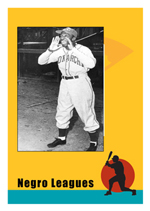

James Bell

(1922-1950)

Cool Papa

James Bell was born in a farming community on the

outskirts of Starkville, Mississippi, in 1901. At age twenty, he moved to St. Louis, joining

his brothers and many other African-Americans looking for a better life

than that afforded blacks in the Deep South. It wasn’t long

before Bell began playing semi-pro ball. In 1922, the St. Louis

Stars of the Negro National League saw promise in the wiry Bell. He

was originally a pitcher but his blazing speed forced a position shift

to center field, and Bell’s full potential became realized.

Cool Papa played ten years with the Stars before the Negro National

League was disbanded. Bell moved on to the greatest Negro League

team in history, the Pittsburgh Crawfords, joining the likes of Josh

Gibson and Satchel Paige.

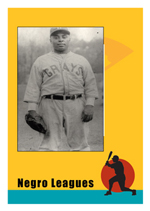

Bell was an excellent hitter, averaging .341 for his career, and a great outfielder, running down fly balls that no one else could get. It was Cool Papa’s speed that made him one of the premiere players in Negro League history. And it was that same speed that gave rise to stories that are difficult to fathom. One such tale was that a ground ball he hit up the middle struck him when he slid into second base. Another had him scoring from first base on a sacrifice bunt. Satchel Paige quipped that Bell was so fast he could turn off the lights and get in bed before the room went dark.

Bell would later tutor such future great players like Ernie Banks, Jackie Robinson, and Elston Howard. In 1974, James “Cool Papa” Bell was inducted into Cooperstown. Were he allowed to play in the majors, he would have entered the Hall of Fame much sooner.